The use of Jeralyn Merritt’s “life plus cancer” as the rhetorical means of making the point that our notion of punishment has run out of room to inflict harm has an analogy in the health care debate. It’s hard to see at first, but reared its ugly head in the final paragraph of Elisabeth Rosenthal’s op-ed:

Today, Mr. Albert, 52, is not happy with the price of his family’s high-deductible Obamacare policy: $2,000 a month. Even so, he said: “The A.C.A. was a lifesaver for us. Everyone in my family has something that could be defined as a pre-existing condition.”

For the lawyers reading this, let me do the math: that’s a deductible under the ACA of $24,000 per year.* It’s unclear where that comes from, or whether that’s all deductible and co-pay is on top of it. There’s no mention of how much Albert pays for his family’s health insurance premiums, But if you add up all the numbers, it’s a lot of money.

“It’s expensive but I don’t have to worry about being excluded from insurance or about bankruptcy anymore.”

It’s entirely up to Jesse Albert whether he considers his peace of mind from having insurance and protecting against bankruptcy for a catastrophic illness a fair trade. The question is whether his peace of mind, which seems to value safety from a very low probability risk extremely highly, is yours, because the way Albert gets his deal is for you to be required to take it as well.

Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, a lowball family premium of $6,000 per year. That’s what he pays out of pocket. If he’s paying such a low premium, he’s not earning a great deal of money, which means his family isn’t eating Osetra caviar twice a week. Are they good with foregoing what that $6,000 will buy them? Perhaps. Are you? You don’t get a choice, because if you do, then Albert doesn’t get his peace of mind.

For this payment of $6,000 per year, Albert buys the opportunity to pay an additional $24,000 out of pocket should he or his family need medical care. That means he’s spent $30,000 before the benefits kick in. Even if he and his family doesn’t go to a doc for anything that year, he’s out the $6,000 premium. But let’s assume he needs the occasional doc visit, the premium buys him no comfort unless it’s catastrophic. Most people don’t suffer catastrophic health care problems every year, so he’s out the premium plus his actual costs because he failed to meet the threshold.

But Albert is okay with this. He’s willing to deny his family whatever the $6,000 premium would buy for the sake of catastrophic protection and his peace of mind. Whether he would survive bankruptcy if required to pay the $24,000 deductible is unknown, but that’s still a lot of money to pay even if he’s a got a big trust fund behind him. But the likelihood is that he will eat into some portion of the deductible long before reaching its apex, and never enjoy the benefit of the insurance part of the deal.

But the point of the op-ed is that “we all have pre-existing conditions,” which is a mantra of dubious worth.

I have interviewed many such people. Renée Martin was thrown into an unaffordable high-risk pool because of an abnormal Pap smear. Lisa Solod got turned away by four insurers because she was on thyroid replacement, an asthma inhaler and hormones — a not uncommon trifecta for women in their 50s. Wanda Wickizer was priced out of having insurance because she had taken Lexapro for depression. Jesse Albert found that he and his family were uninsurable because he had once had a benign skin cancer and a bout of hepatitis C, even though his immune system had cleared the virus.

According to the op-ed, one in seven are turned away from insurance for pre-existing conditions. This is hardly an insignificant number, and health insurers use their “proprietary” basis for deciding that your unsightly blemish constitutes a pre-existing condition for the purpose of throwing you out of the pool. It’s a profit center, by reducing their probability of having to pay out a dime of the premiums you would otherwise pay.

For some people, it’s not insurance at all, as the need is known and established, and they’re buying a million dollars of health care for a pittance. The other premium payers make up the cost difference, plus the carrier’s profit. Contrary to the arguments made to slam those with pre-existing conditions, they are not necessarily unworthy of care, or suffering their own poor choices. Nobody asked to get t-boned by a tractor-trailer that ran a red light. Nobody deserves getting colon cancer.

And even if they did something foolish, like ate donuts for every meal until their pension vested, should we leave them to die in the streets?

But Albert’s peace of mind comes from somewhere, and that somewhere is the six of seven who, miraculously, don’t fit the insurer’s pre-existing conditions paradigm. That includes the very healthy 30-something with student loans and hungry mouths to feed, who may not share Albert’s desire for peace of mind. She may prefer to buy shoes for the kids. Or even for herself.

She’s allowed to want to use her money for whatever she wants, even if you find it frivolous. Even if it means that Albert doesn’t get what he wants. Maybe she’s happy to pay an extra sum of money so that Albert can enjoy his peace of mind. Maybe not. Maybe if Albert’s family was suffering catastrophic health care expenses, she would be moved by the story to give up her Manolo Blahniks, but maybe she isn’t willing to do so just to provide Albert the comfort of knowing that it’s there just in case he needs it, which he probably won’t.

But the AHCA exacerbates the problem for all involved, removing 23 million people from the ranks of the insured, denying them the opportunity to spend $30,000 a year should they suffer a catastrophic health care need, and a mere $6,000 per year plus out-of-pocket costs if they don’t. The options we’re fighting over, that Rosenthal writes about, are life or life plus cancer.

*Edit: As noted in the comment below, this amount may be the monthly premium (which makes more sense than deductible) and I misread the quote. The 2017 max deductible and co-pay for a family is $14,300. So, in tandem with premiums of $24,000 per year, this means that there is no benefit to be gained until a family expends $38,300 rather than the $30,000 I’ve assumed. My apologes for the misreading.

Discover more from Simple Justice

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I read the quoted paragraph as saying that Albert pays $2000 per month in premiums. This reading is supported by the fact that deductibles are typically set on an annual basis, not a monthly one.

So, he’s paying $24,000 a year in premiums and still has the unquantified “high deductible” do deal with should he or his family ever use their plan.

I think you’re right, and I’ve added a footnote to correct my misreading.

My reading is that the premium is $2000 per month, the high deductible itself does not appear to be mentioned. The deductible for a high-deductible family policy, I think is in the ballpark of $12000. So the numbers are tilted even more against Mr. Albert — $36000 in out-of-pocket expenses before health insurance kicks in.

It doesn’t really seem like either party even cares about coming up with a solution to this problem.

See the other rob’s comment. Your comment came in before I posted TOR’s, but I think both of you are right and I was wrong not that it alters the analysis for the numbers are off.

Lawyers and math. Your eyes probably glazed over when they spotted a number, making the words around it go fuzzy. I think that’s what’s called “fuzzy math,” right?

Thank goodness we sometimes make up for it in other ways.

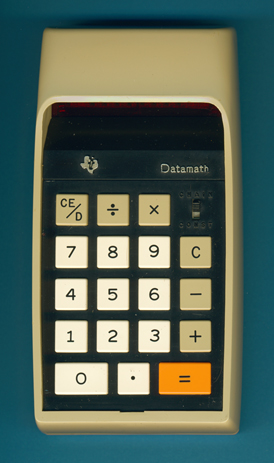

The day TI invented the calculator was one of the most important days in legal history.

I don’t know about lawyers, but us engineers used to bow toward Palo Alto in honor of the HP scientific calculator line. I got rid of my stinking TI-58C calculator after misreading the decimal point on its teeny tiny display during a final and getting an entire problem wrong (that professor didn’t believe in partial credit). I saved my earnings all summer and bought the pinnacle of scientific calculators: the HP-41CV, which lasted me a solid 20 years before I stopped using it.

TI can bite me.

The TI 2500 DataMath was awesome, and you’re calculatist. I had my first one for exactly one day before it was stolen.

I’ve been to Palo Alto. A strip of coffee shops, organic food restaurants and people who deliberately look like homeless Jesus. Bow if you must.

My first electronic calculator was made by Rockwell. The people who helped build the Space Shuttle. It hissed when you turned the power on and during the quiet of exams you could hear it across the classroom.

In the legal system the life sentence is literal and the cancer figurative. In health care the life sentence is figurative but the cancer is literal. Protecting against either is expensive – despite the sixth amendment, is there any state that over funds its public defenders? If health care were a constitutional right it could be defended as effectively as the indigent accused are.

The healthy 30-something is allowed to use her money for whatever she wants unless the government mandates otherwise: driver’s license, registration fees, taxes, health care. As of 2017 there is now a political majority who thinks that the ACA is not cost-efficient and are trying to unravel it without angering so many they get thrown out of office. While Medicare/Medicaid are popular, the ACA has a personal, visible price that must be paid monthly in an insurance bill instead of tucked out of sight into federal debt payments like other expensive entitlement programs. I don’t know whether that make people less charitable or gives them more accurate costing information to make a decision.

On a side note – why would Rosenthal choose Albert’s $2k/month as an example to prove her point? According to Kaiser Foundation’s calculator, an unsubsidized silver level family plan costs $901/month in Texas, a state as hostile as any to the ACA. If she has talked to as many people as she says she has, she ought to have a less eye-poppingly pricey example. Perhaps it is an indication that most journalists have math skills equivalent to most lawyers.

We’re not doing very well with indigent defense. If healthcare was a constitutional right, perhaps we would all be dead. Or broke.

After a decade(!) of reading your blog and a believer in universal health care it disturbed me to write that sentence.

With some fiscally prudent caveats, I too am a believer in universal health care based on a single payer system. It will be expensive and unsatisfying to many (what? I can’t try ten billion dollar unproven cures?), but it’s better than any alternative.

I too am a believer in universal health care based on a single payer system. It will be expensive and unsatisfying to many

That seems the only logical end game. The terms we use to discuss this are horrible. It’s clearly not insurance, as practiced anywhere else. Insurance is mitigating risk with a payment which is in proportion to the risk. Someone that’s a garauntee to file a claim wouldn’t and shouldn’t be insurable for anything less than the cost of their claims.

Rather, for these folks, we talk about insurance when instead it’s more accurate to speak of it in terms of distributed cost for benefits covered in an aggregate pot.

If we are keeping the pre-existing condition group in the insurance pool, why does it make any sense to put them in an insurance market where profits are removed from the system? Those profits represent treatments or medical products.

Non-profits keeping the gov on their toes seems like a good way to give people options, but for the life of me, I don’t get why for-profit insurance companies should siphon money out of this system.

People don’t want insurance. They want health care without having to pay on the nose for it. They don’t care how they get it, but that they get it.

Using the word “insurance” skews the entire conversation in the wrong direction. We would be far better served if we somehow managed to quit using the word altogether when it comes to health care, and had a conversation on how much health care should cost and how much each of us should pay.

The 30-something is still part of the greater whole of society that decided long ago that she shouldn’t be able to walk in her Manolo Blahnicks over the uninsured having a heart attack, to get into the ER. The logical inference is that society is always going to pay for a certain level of care via taxation.

Whether that taxation is general as it was pre-ACA or direct and specific as it is now, there’s an agreement as to what kind of society we are. Now, we’re just haggling over the price.

I’m not sure where you’re going with the first part but the second paragraph is the real issue. As long as hospitals that receive federal money are required to provide emergency treatment to people regardless of whether they have insurance there is no meaningful way to opt out of the system. It isn’t about whether the 30 year old cares about Albert, it’s about whether or not she’s allowed to be a free rider.

To be a free rider, she would have to suffer a bit of the indignity of getting chased down for the bill (and possibly having her bank accounts seized or her pay garnished to cover a judgment) or going on Medicaid, which may not be an option. It’s not that she can’t free ride, but that there’s a price to pay for it. If you’re going to end up bankrupt anyway, the price is negligible, but that usually not the case.

The price, and how and by whom it gets paid. But there are a lot of things that are not heart attacks, but that eventually become untreatable because uninsured persons do not seek care. The ACA did not eliminate this problem, because there were still great numbers of uninsured who could not afford coverage.

Pre-existing conditions have always been utilized as a red-herring first to promote the ACA, and later to denigrate the AHCA. There were about 270,000,000 Americans with health insurance prior to the implementation of the ACA in 2014. Pre-existing condition denials never numbered more than 375,000 in any single year, prior to the implementation of the ACA. That means that fourteen thousandths of a percent of the population that wanted health insurance were denied. They were usually absorbed by the State’s high risk pools. For those that weren’t, the HHS rolled out a federal alternative to the State’s high risk pools, in 2010, in order to cover the spell until 2014 when the ACA was fully implemented. HHS expected as many as 350,000 enrollees but never surpassed 115,000.

And yet, this is what everyone is fighting over, bad and worse, based upon sad stories while ignoring the vast majority of people who have fairly expensive insurance that’s functionally useless.

“According to the op-ed, one in seven are turned away from insurance for pre-existing conditions.” And as usual, the op-ed entirely omits the cause: We (Congress, to be exact) are to blame for this.

Insurers are there to make money, which they do by selling insurance. They want to sell more insurance to make more money. And anyone in the commercial world will tell you that insurance agencies write risky policies all the time–provided that they charge premiums to match.

The reason that insurers will refuse to sell policies in this case is the same reason that people aren’t rushing out to build new rent-controlled apartments: we have passed legislation which prevents them from charging enough to cover their perceived risk. Since they would unsurprisingly prefer not to lose money, they don’t write the policies at all.

Time was I would be surprised at such a stupid journalistic lapse. Not anymore.

Community rating underpins the high risks. That’s the point of ACA, that everyone is charged the same, regardless of health, with the mandate that all the healthy people were required to buy insurance they wouldn’t use to pay for all the unhealthy people who buy insurance knowing their use would exceed their premiums. When the mandate was gone, many healthy people went uninsured because it was a horrible deal, leaving those left to pay the extra cost of the unhealthy.

It’s v. easy to heap scorn upon and criticize a sitting president. Why should insurers be entitled to make any money at all? What is so special about them. What do they produce but a bunch of paperwork, telephone-tagging, and stalling shenanigans. They pull out the “fine print” to show why your claim cannot be paid. It’s the oldest two-step trick in the book. The only people worse are stockbrokers who pump and dump, and lawyers who baldass lie about billing for hours not worked. Oh, and then there are polyticians who make promises they know they will not be able to keep. And miles to go before we sleep.

I long for the good old days when, the story says, the doctor would come to your house when you needed him, and you could pay in apples or chickens. I’m guessing that in practice this scheme delivered an inconsistent level of service to the patient, and most likely caused injury or death in some cases, but I’d prefer that to the uniformly terrible results I’ve seen recently.

You have chickens?

I’ll get some.

Separate and apart from the theme of your piece, your need to self-flagellate, by continued consumption of Satan’s East-coast paper of record, is troubling. I suspect you could achieve superior results with a short jaunt towards 8th Ave. I understand the area offers a fine selection of dominatrix services at reasonable rates. 😉

In any case, as I’m sure you’re aware, Ken White (as have you), on multiple occasions, taken the press to task for grossly and repeatedly mis-characterizing legal issues and/or getting them just plain wrong. Of course, it’s not just legal issues the press gets wrong. Almost any detail, on any topic, requiring a journalist (or fact-checker) to spend more than 15 seconds Googling an answer is seen as a waste. (The time is considered better spent coming up with click-bait headlines, like the infamous “Headless Body in Topless Bar”).

==============

As an aside, true story: A broadcast journalist called a local courthouse to check the status of a trial in which the defendant had jumped bail after the start of proceedings. The court clerk informed her that the defendant “was convicted in absentia”. To which she replied “where’s absentia?”

==============

But The New York Times deserves special contempt, as it continues to promote the fiction that some form of separation exists between hard news and opinion.

While Robert D’s side-note already questions Elisabeth Rosenthal’s choice of example, I think it goes beyond that. Although Ms. Rosenthal’s piece is clearly labeled as opinion, it’s blatantly structured to gin-up the faithful. For instance, where you quoted…

“Jesse Albert found that he and his family were uninsurable because he had once had a benign skin cancer…”

It’s either benign or it’s cancer, not both. Maybe it was pre-cancerous (i.e., the cells were dysplasic), but that’s not the same as cancer. I’m sure Ms. Rosenthal knows the difference. Saying Mr. Albert had some benign growth(s) removed lacks the emotional impact of the big-C. Words matter. And continually doling out disingenuous hyperbole, and/or just plain BS, erodes credibility.

Having just eliminated the position of Public Editor (see “New York Times Will Offer Employee Buyouts and Eliminate Public Editor Role” – https://nyti.ms/2roD7vr)* — saying that social media will adequately act as a substitute watchdog — what limited, internal oversight that existed is gone. You do the math. C’est la vie.

——–

And speaking of math, regarding calculators, my son had an HP, his college roommate had a TI. (My time at university predated the pocket calculator era). While visiting, the roommate asks “what the heck is RPN?” (Reverse Polish Notation). To which junior replied “if you have to ask, stick with TI”. (The roommate thought RPN was someone’s idea of a bad Polish joke).

I was told that almost everyone studying the hard sciences had an HP, most others had TI. Although, they’d occasionally run into a Phys-Ed major who had a Bowmar Brain.

——–

*I know you prohibit links and it will be removed. It was solely provided for your convenience.

Had you written this on the day of the post, it would have stood a good chance of getting trashed because reasons. You’re right about the benign cancer. I completely missed that.